Reconciliation, Eating Disorders and Aboriginal health

National Reconciliation Week is a time for all Australians to learn about our shared histories, cultures, and achievements, and to explore how each of us can contribute to achieving reconciliation in Australia.

The ultimate goal of reconciliation is to close the gap and build strong and trusting relationships between Aboriginal Australians and other Australians, as a foundation for success and to enhance our national wellbeing.

Elizabeth (Liz) Dale, from the University of Wollongong, gives her insights into Aboriginal health and eating disorders.

My thoughts on Reconciliation, Eating Disorders and Aboriginal health

Before we start, I am going to be using the term Aboriginal Australians to respectfully refer to people of both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. However it’s important to remember that when discussing mental health needs and experiences of Aboriginal Australians, we need to keep in mind cultural and community diversity within the population.

Reconciliation is an important time to sit and reflect on our journey; where we’ve come, where we’re going and what we have to do to get there. This year, Reconciliation Week is celebrating 20 years and the theme is ‘in this together’, which is appropriate given the global pandemic we are all facing.

When discussing mental health issues, the theme serves to remind us that at the end of the day we’re all human beings, sharing beautiful lands together and that disease and grief don’t discriminate.

For me, reconciliation is an opportunity for people to take a moment and appreciate alternative cultural views, to reflect on life through another’s perspective and to build respect for the fact that people’s experiences (especially mental health) are shaped by their cultural identities and circumstances.

Within an Australian context, it’s an invitation for the nation to work together to achieve justice and equality for all at all levels, including social and community, organisational, local and state government, and federal levels.

Practically, this means things like the mainstream culture, recognising and committing to changing any thoughts, feelings or actions that marginalise Aboriginal peoples and cultures, and for Aboriginal peoples, continuing to advance through advocacy our cultural knowledges within our places of work, education, and all of our social and community connections that involve both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples.

This also requires individual level commitment to challenge things we see, or feel that aren’t equitable or just. It’s also about cultivating an appreciation for Aboriginal culture and embedding our culture into all societal and community domains.

Aboriginal Australians and eating disorders

Eating disorders don’t care about a person’s race or ethnicity; they don’t discriminate. But sadly, the current approaches to eating disorder care do discriminate. Current eating disorder treatments fail to seek out different cultural perspectives, or build culturally meaningful approaches to care. With over 13 years of clinical experience, I witness how very little consideration is given within psychiatry and psychology to the impact of a person’s culture and their environment in terms of what causes and maintains eating disorders. Also, importantly, how a person’s culture and environment impacts their treatment and recovery options.

Even though there are common diagnostic symptoms underpinning the various types of eating disorders, everyone has their own unique experience and discourse. Therefore, to help a person adequately, there needs to be an understanding of this with treatment models reflecting this accordingly. This as opposed to the traditional western biomedical approach for treating eating disorders.

Over the years I have watched friends, family, and my own Aboriginal clients, struggle to connect with western treatments. And this includes non-Aboriginal clinicians who show a lack of understanding of cultural recovery principles for health and wellness.

Eating disorders and body dissatisfaction in Aboriginal populations

Generally, there’s a lack of research and recognition of Aboriginal populations experiences with mental health issues, and this includes eating disorders.

Aboriginal people (like all Australians) experience the pressures of our current diet culture. We’re constantly bombarded with media advertising products and new health ‘trends’ including diets, exercise regimes and images of ‘perfect’ bodies — messages that disempower all of us. However, unique for Aboriginal peoples are that when these messages are paired with the existing negative, racist and stereotypical public portrayal of Aboriginal people, this creates a toxic internal discourse that is damaging to our sense of identity and belonging.

This is all compounded by socioeconomic disadvantage that many Aboriginal people experience, especially those living in rural and regional areas, where quality of life is lower and support and services are harder to access.

When it comes to how Aboriginal people experience body dissatisfaction and eating disorders, we need to remember:

- Many mental health issues experienced by Aboriginal people are influenced by social determinants and are a symptom of colonial trauma. As such approaches to recovery need to be practical, holistic and multi-systemic.

- We need more research into eating disorders among Aboriginal populations.

- There is a lack of culturally appropriate screening, assessment, and interventions.

- The mainstream health care sector doesn’t view, or treat, Aboriginal health and wellbeing according to our holistic model of Social Emotional Wellbeing (SEWB).

- Racist stereotypes and stigmatisation, portrayed through the media, influences our sense of identity, which in turn impacts our body image and body satisfaction.

Closing the gap

Closing the Gap is more than achieving equality of life expectancy, education and employment for all Australians. This is a political concept and lacks the depth of understanding of what Aboriginal people actually want, which is self-determination, equity and to enjoy excellent health and wellbeing.

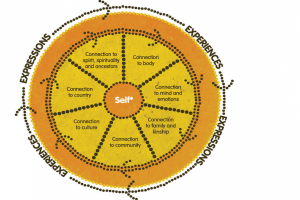

For Aboriginal people, health is more than the absence of disease; it’s about connection, strong cultural identities and wellbeing. And while health is an area that’s often referred to when it comes to the gap, by focusing on merely number deficits we fail to focus on the strengths of Aboriginal approaches to health and wellbeing, which looks at a whole system of wellbeing, including social, emotional, spiritual, and cultural factors while also recognising the sacred connection to land, culture, spirituality, family, and community and how these things impact on a person’s sense of wellness. This is seen in the SEWB wheel, as shown below.

Image: The SEWB wheel, where the Self is not the self as known in a western sense, but where the Self is experienced from the communal perspective

While it’s important to highlight the disadvantage, having a deficit discourse as the dominate narrative, especially when it informs health care policy and practice, is what I believe to be the fundamental reason that research and treatment has not progressed in favour of Aboriginal people.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health and wellbeing is still, sadly, very much a political issue. Decisions underpinning the allocation and provision of our health care is largely determined by a bipartisan agreement, which gets passed from one government office to another without being evaluated or updated. At this level of decision-making the emphasis is on statistics and getting the numbers to look good, instead of being concerned with the type and quality of care that’s being delivered on the ground. By treating us like a statistical exercise, rather than taking the time to acknowledge our strengths, the fact that we have our own psychological Knowledges is missed. There is an arrogance within western psychology that their knowledge is superior to ours — this totally discredits other cultural perspectives and knowledges.

SEWB is our psychology – it explains how we assess, conceptualise and treat mental un-wellness. It illustrates our holistic way of life and the need for us to be in harmony with many aspects of health and wellness, not just the absence of disease as is the common approach of western models.

It’s also important to note that our health also suffers due to the enduring legacy of colonisation. In the context of eating disorders, we know from our research that eating disorders are caused by and perpetuated through poor psychosocial quality of life and social determinants, such as housing conditions and accessibility, unemployment and educational opportunities as well as through high rates of comorbidities such as depression and anxiety.

Eating disorder health care, for Aboriginal peoples could be enhanced by embedding Aboriginal knowledges and adopting the SEWB model to create culturally safe assessments and treatments. SEWB is holistic and recognises the importance of health within all domains of life (spiritual, physical, psychological, interpersonal etc.), which we know are all invaded by eating disorders.

The power to improve knowledge, develop cultural competence and furthering reconciliation

Organisations like Butterfly Foundation are in a powerful position to help achieve reconciliation, after all, reconciliation happens in the head, heart and actions of individuals and organisations like Butterfly. Some ways organisations can influence culturally sensitive treatment and to promote reconciliation include:

- Cultivating a culturally sensitive and informed organisational culture by being inclusive of Aboriginal art, concepts of health and wellbeing, languages, and peoples into all levels of the organisation.

- Establishing meaningful partnerships with Aboriginal communities and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHO).

- Funding research into indigenous knowledge, including our experiences of eating disorders and treatments.

- Helping to grow the Aboriginal health care workforce, by employing Aboriginal people and providing appropriate training and mentoring.

- Critically reflecting on how the organisations can shift its mainstream power and presence towards one that is more equitable and inviting to other cultures. For example, including culturally appealing images and languages on websites, and embedding Aboriginal SEWB knowledge within marketing and self-help materials.

Better understanding for better treatment options and outcomes

While we’ve come so far, we still have a long way to go. One way we can close the gap and make a brighter, more inclusive and culturally diverse future for Aboriginal Australians is with more research into this area.

Clinicians are also in an important position when it comes to creating better treatment options and outcomes too.

Firstly, there’s the importance of acknowledging the power inequality between the clinician and patient — something that is often forgotten, whether working with the Aboriginal population or not. Power inequality continues to marginalise Aboriginal health and wellbeing. Also, pushing a western model on an Aboriginal person disempowers them, perpetuates illness and further ingrains inequality — all of which then further fuels mental illness and prevents recovery.

Clinicians can also take the time to learn about the strengths of the Aboriginal cultural model of wellbeing and how SEWB is a holistic way of working with an individual. The idea of cultural diversity and individuality are also important. What works for one Aboriginal patient might not work for another.

Clinicians need tertiary training in Aboriginal Knowledges, and not merely a token way. We need more openness to learning, from clinicians and their organisations with greater access to resources so they can become more culturally competent.

Further, we need more qualitative studies to grow a body of evidence informed by Aboriginal voices, perspectives and experiences. Right now the research isn’t there, and what is available are mostly deficit focused statistics.

But mostly the best advice I can give a clinician is to ask, listen and learn. Don’t assume.

About Elizabeth Dale

Liz is a descendant from the Worimi Nation. She is currently enrolled in a Doctor of Philosophy (Clinical Psychology) at the University of Wollongong. Liz works as a research assistant with the National Health and Medical Council Centre of Research Excellence: Indigenous Health and Alcohol and is a casual lecturer for the University of Wollongong Graduate School of Medicine and School of Psychology Departments.

Liz has over 13 years of experience working in a range of government and non-government and clinical settings. Her experience spans youth and adult homelessness, family and relationship counselling, mental health disorders, drug and alcohol, gambling addiction, eating disorders and intergenerational trauma.

Liz has a deeply personal interest in understanding eating disorders as she has close family and friends (both Aboriginal and non-Indigenous) who live with eating disorders; some still chronic, some recovered and some sadly losing their lives to it. She’s passionate about helping to advance the field towards better care and treatment for all people who experience and eating disorders.